On my latest trip to Central Otago, I turned right out of the airport, and never stepped a foot in Queenstown – heading out into wine country, and out to the furthest point first. Over the Crown Range, stopping in at the Cardona Pub for a pint, and then on to Wanaka for a first appointment at a wine label that has impressed me over the last few years. To meet with founder and owner Andrew Donaldson of Akitu. We head straight out into the vineyards on a lovely late Spring afternoon.

Andrew Donaldson: One was planted in 2002 and the other in 2003 and 2004. 100% Pinot Noir, but six different clones on two different rootstocks, because there are very distinct soil types. Essentially twelve plants in the vineyard. And this is probably one of the most marginal of sites — certainly whilst we were appraising it — planted in Central Otago. There are six sub-regions of Central Otago – from hottest to coldest – Bendigo, Cromwell Road, Bannockburn, Alexandra, Wanaka and then Gibbston which is the coolest. Alan Brady at Gibbston and Rolfe Mills at Rippon were two of the earliest sites, and that was before Stuart Elms at Bannockburn. It’s interesting that two of the sub-regions that were first planted, were actually the two coolest sub-regions of Central Otago.

Our marginality is a combination of things. One is altitude — we’re at 380 metres above sea level up here, and proximity to the Alps. Wanaka is the closest sub-region to the Main Divide, and whilst we get the benefit of a little bit more rain, we do not get the moderation of the lake itself — which Nick at Rippon does. Our original business plan was that we would probably have one failure in six — and we’ve never had a failure. We think there’s about three reasons for this. The first one is the mountain behind us that protects us from the southerly. The south-westerly we get but that gets funnelled around and we miss the worst of it. The south-easterly is still very grim, and all easterlies in this part of the world are just horrid. We’ve got a nice slope so we get some cold air drainage.

We benefit greatly from our soil fertility. You don’t want too fertile soils for growing Pinot but it seems to be about perfect. The things that it seems with Pinot, is the more marginal, the more adverse the conditions, the better the plants behave. More interesting and more unique flavour profiles come through from the most marginal sites. If you go to some of the other sub-regions in hot vintages, and you tend to get past that point of peak interest. Much more of a fruit story, whereas our signature is very fine acids.

One of the critics that came through here not so long ago, was looking at Bendigo – and there’s some great producers up there — but their comment was “Up there they really make Pinot for Shiraz drinkers”. Which is a pretty interesting summary. And that’s not what we’re after.

We can have a much longer hang time without our sugars turning to alcohol. Pinot has these two ripenesses — it has the sugar ripeness and then a phenolic ripeness. We end up with a very soft ripening period without our sugars taking off. If you were somewhere like Bendigo or even Felton Road, your sugars would still be sneaking up — and that will eventually force you to pick. And we would prefer to have that hang time, with sugars stable, and just let that phenolic ripeness catch up. If you hit that sweet spot then you end up with a year like our 2016 was.

We look at Pinot as this three-legged stool of fruit and tannins and acid, and acid being the most important. If you can get those other two legs in balance with your acid, then you end up with that really interesting story.

WineFolio: One thing that is also interesting, is that here you have that mixture of being able to grow great Pinot, but also have the sheer beauty of the surroundings. Somewhere like Martinborough let’s say — as another Pinot region — doesn’t have this scenery.

AD: I think that Martinborough does, in the right vintages, produce the most extraordinary wines. And I think there’s some wonderful winemakers there. But they do seem to be capacity-constrained, and they have their own set of issues there.

WF: And often, I find, that their white wines are every bit as good as the Pinot. Like Craggy Range Sauvignon Blanc, or Dry River’s aromatics.

So why here — this location for you, and Akitu?

AD: For me? I was born here. Our family is from Wanaka. I lived overseas for thirty years, and I always wanted to find a reason to come back. Not even to Central Otago, but to Wanaka. And when I left there was sheep farming and tourism. But then, in about ’96, something like that, Central Otago became the most interesting place to grow my favourite varietal. And I’m looking for a reason to come back here…

I owned another piece of land over there, but there aren’t too many sites here in the Upper Clutha Basin. You’ve got Rippon, Aitken’s Folly, us and Maude. Three of us have got a slope, which is important as frost is our biggest risk. To find a piece of dirt that has a slope and is pointed in the right direction — because this is due north — and has some protection from the southerly, is not easy. So there will never be a lot of vineyards in this part of the world. And land prices up here are just insane. There’s no way I could afford to buy this land today and plant it in vines. No-one could.

There are some slopes — do you see those ones over there? Every time Dan – who is best mates with our winemaker PJ Charteris – sit down with PJ, they’re always looking over there. Because those slopes there have got fabulous protection! Unfortunately it is above the Outstanding Natural Landscape line, so whilst you’d be able to plant a vineyard, that’s about all you’d be able to do. You could do Chardonnay. You could do something that’s not too dependant on soil.

This valley is obviously glacial, as you can see. We’ve had three periods of glaciation through here. 38,000 years ago you would have been under about two kilometres of ice here. And that last glaciation did a number of things. One thing it did was formed the lake. Everything from the front of the vineyard to the lake, if you look at it has this wavy character to it. That is all gravel. As the glaciers retreated all the gravel that has been ripped out of the Alps. If you go out into the middle of that paddock — or that one, or that one — and dig a hole, and after about this much you’ll just find gravel. And that will go on for 20 metres there, and 9 metres there, and 25 metres there.

It’s very free-draining and very homogeneous. This is Mt Barker here and it is a piece of 250 million year old fractured schist. So that’s a piece of rock that the period of glaciation couldn’t move. It has that classic shape that the french would call ‘a resting sheep’ — a ramp up one side as the ice ground it up, and then comes down the front to create a cliff face. Mt Barker is another one of these knobs. You’ll see huge chunks of rock surrounded by powdery stuff which is windblown loess. That layered fractured schist is flecked with quartz, and it is the quartz that contained the gold, which gave rise to the Clutha Gold Rush. The Clutha River Gold Strike in 1864 is the second biggest gold strike in the world.

We’re shoot-thinning today, and we just finished the bud rubbing, using our new machine. And the vineyard crew have done the once-a-year herbicide spray — which is the last year we’ll be doing that. But about eight inches of growth has happened in a week. We had so much rain this winter and we have so much retained soil moisture that it was only with those two or three days of warmth, and things went Kaboom. Once we shoot-thin and take all this off, it just goes crazy. Next week it will be up to the wires. The last two years we’ve had these late Spring wind events that just turn up out of nowhere. On our exposed ridges we took a hit big time. We lost 10% of our shoots

WF: What are the main differences between A1 and A2?

AD: Three main differences. One is clones. In all but the last vintage, the A1 tends to be one clone from one block, which we’ll come to. Whereas the A2 is more of an omni — it covers more of the vineyard than just that one clone. We have six clones and there are six blocks, but they’re not planted block by block. We have 114 and 115. We have 667 and 777; and then we have UC Davis Clone 5 which does very well with us — and then we have Abel. We have two sections of Abel – about 25 rows in B Block, and then F Block is all Abel – apart from the first ten rows. Our Abel fruit has gathered a reputation for being some of the most interesting fruit in the country.

F Block isn’t orientated due north and it doesn’t have as much of a slope. It is the most east-facing block and it produces our most graceful and elegant fruit. Nigel Greening used to rent my house when he was building his new one and he used to say that there’s something special about this particular block. We would normally get our A1 fruit from this block, and in cold years we get it from the Abel in Block B. Block F is always the last block to pick, and it is probably the last pick of Pinot in Central. There would be a few in Gibbston as well, but we would often pick at least three weeks, if not four weeks later than Felton Road.

That hang time is really important and what we think is happening here is from those very cold nights, and then the very gentle morning sun rises and hits this block absolutely flush. The hottest part of the day in Central Otago is 5.30 to 6pm at night. And by then the sun is way over here. And there is a spur of schist that comes down here, and there’s something special about it. This block is the first of the three components that makes the A1 different from the A2.

We make our wine at Maude with Dan and SK – PJ and Dan are very old mates, and were both, at different times, Head Winemaker at Brokenwood in Australia. And about ten years ago Maude started to get very interested in Whole Bunch. And we’re constantly experimenting with whole bunch. So the second component is about 35-40% whole bunch depending on the lignification of the rachis in any year. That’s typically about double the whole bunch that will be in the A2. So there’s a lot of other phenolics that have gone into the ferment, and there’s more structure. If you get really good lignification in your rachis and use that for whole bunch you pick up some flavour notes that you wouldn’t have done otherwise. We also don’t crush any more, so everything is either whole bunch or whole berry now.

And the last component of the difference between A1 and A2 is that we tend to carry more new oak. But we’re not huge fans on oak, so we’re pretty parsimonious with new oak. We try not to use first-use new oak on anything that was going into the A1. But we would end up with something like 20-25% new oak. We don’t know what’s going to go into the blend, so hopefully we’ll end up with second or third use oak. It’s intentionally a much more structured wine. We’re trying to hold that classic Central Otago fruit story back a bit, in the A1. We’re much more disposed to make a more Burgundian style.

WF: You see that in Nick’s wines at Rippon, I think.

AD: Absolutely. And whilst our wines are very different from Nick’s. He will stress his plants much more than we would. He doesn’t irrigate, but I’d guess he probably gets 800mm of rain a year, whereas we are 4kms away and just get 680mm. And go around the corner and you’re into low 600s and by the time you get to Felton Rd you’re at 450mm.

WF: What are your thoughts on biodynamics?

AD: We only do two things here which are non-organic. We’ve always under-row sprayed. But we have cut that down now, to one a year. We’ve bought a whole lot of kit so we can move to under-row cultivation. There’s a lot going on at the moment about no-till. We will end up with a little bit of till, but we’re going to be very careful about it. We’ve got this crazy device that’s got these little rubber fingers that de-bud but we’re noticing that it also flattens out the weeds really well. The other things we use is if there’s any moisture at bunch closure time, we use a non-organic spray then.

We’ve measured the soils here and we have never fertilised, and never used compost — but we have no discernible change in our soil profiles year after year. Even with a single crop that is sucking out year after year. I’ve just got a new Vineyard Manager, and George was one of the lead Vits for Craggy range at Martinborough. One of the reason we could attract him was our organic transition which we are starting this year.

We don’t need a lot of cover crop — probably only once every ten rows. We’ve used about five different seeds in this row, and it is just starting to strike. Most of what we put in is to attract the predatory insects that deal with leaf roll. We don’t really need it for the carbon. We’ve got a fair amount of clover in the vineyard. What we have done is a lot of work in terms of mid-row sub-surface. Depending on soil porosity we’ll be either doing 300 in and 300 down, every second row. The thing about sub-surface is that you use dramatically less water. And then we can get in and under-row cultivate. This is the first block we’re going to do, and it would be done now except the piping we ordered a year ago hasn’t arrived in the country yet.

We’re just starting to understand how these soils behave, and their interaction with plants, and it is really fascinating. We’ll go organic. We won’t go biodynamic, I can’t imagine. I’m much more interested in a regenerative operation than biodynamics. You have to really ‘believe’ in it. My view is that the biodynamic viticulturists just do pay more attention. They’re caring for their plants more. It’s a real symbiotic relationship between humans, plants and soil.

We leave the vineyard an head off to try the finished wines. Andrew tells us about the recent vintages…

AD: Every year is a different year. I’ll give you an example — our sweet spot is about 4.5 tonnes a hectare. That means we’re about 54-56 tonnes a year as a long-term average. 2016, which was until 2019 turned up, our best year and produced our most classic and best wine. We picked 56 tonnes. 2017 turns up and we have an appalling fruit set. We did almost no thinning of any description, and picked every bunch we could find – 28 tonnes. 2018 – which is in that glass — was the craziest vintage we’ve ever had. 250 growing degrees days over our long term average. The long term average here is 1008, and we were like 1260. So a ridiculously hot year. Huge berries and we picked 68 tonnes. So you go from 28 to 68 in a year. That’s the kind of craziness in such a marginal environment.

A couple of years on from releasing the ‘18s and you actually start to think this is an interesting story — and a couple of the European critics have said that of the 2018s, of Central Otago – that ours is the best, and will stand the test of time as well as anybody. It was chaos — people were forced to pick — some pretty big labels — five weeks early. It was unrelenting — every day, and it wasn’t much fun.

2019 – really from the moment we picked it, it was really special. 2016 we thought was the best ‘classic’ wine, but the interesting thing was that when we put ’16 and ’17 next to each other at wine shows — the punters would always prefer the ’16 — because it was classic. Lovely rounded shoulders, great acid line, lovely balance. And all the winemakers would go for the ’17. In the end I stopped one and said “Why is this happening?” And they said “Because I can feel the pain in it!” — which is a great line. And I told PJ that and he said “Yep, that’s exactly what I would say” As PJ says — in 2016 there was nothing for a winemaker to do. In 2017 he had to try every trick in the book.

The ‘17s have an intensity and darkness about them, because the berries were tiny. A very concentrated style and colour. So any of those guys who tend to be a bit heavy on the press, it would be coming out looking like bulls blood. There’s two years that I can taste and say “That’s ’15 and that’s ’17” and for me that’s pretty good! I can identify our ’15 every time. And I love our ’15. New Zealand critics hated our ’15! The europeans adored our ’15. Because it was so light in colour, yet it had structure. It was like this little ballerina, perfectly formed and it just danced. People were snarky about it and I was like “guys you’re missing the point — you don’t have this big thing”.

WF: Funnily enough — the first time I talked to people in New Zealand about Pinot Noir in exactly that way, I was told I was an idiot! hahaha.

AD: The way that I always characterise it, and I don’t say it often as you get smacked around in this part of the world for saying it – I just think there are so many critics in New Zealand that only have a prism that’s that wide, because that’s all that they’re exposed to. If you’re sitting in 67 Pall Mall in London – your prism is THIS wide, and you see everything in entirely different levels of graduations. And here they just go ‘boom’ and I’m like “What the heck are you talking about?”

WF: Absolutely. It’s like “well this fits in my box” and anything that is outside that must be wrong. I’ve already found that, with judging; and to a certain degree, with reviewing and critiquing wines in New Zealand.

AD: Do you know Matthew Jukes? I’ve known him for a very long time. I knew him socially before I had anything to do with wine. And he’s a pretty tough scorer. He’s been a little bit reserved in his assessment of our wines, I have to say. And this year he came to the wine show and I had a little chat with him. He fell in love with our Pinot Noir Blanc, which is a white wine made from Pinot Noir. He said “I’ve tasted 6000 wines this year so far, and there’s two of them that I cannot get out of my head. One was this wine I tasted from Austria, and the second one is that wine there. There’s something about it that just makes it completely unique” His review was quite gracious — “Keen-edged with acidity underpinning the beguiling fruit and oak and lees both playing subtle supporting work, the dramatic terroir shines through with laser accuracy, and it is this setting that you are drinking. I urge you to taste this wine — there is nothing like it on earth”

So, for a guy from here, who is trying to crack it — to have a guy like that say “there is nothing like it on earth”, you just go wow! But do you know what – do you think anyone in this place is interested in that review? “Who’s Matthew Jukes!?” He only writes a wine column for the biggest selling newspaper in the world. Anyway – ’18 or ’19?

WF: The 2018 for me. The 2019 has more elegance and a smoothness to it, but there’s something about the personality, and juiciness, of the 2018 that talks to me.

AD: In 2012 there was just the black label. So the brief for the white label wine was “I want you to make us a wine that you don’t need to write about, and you don’t need to talk about. All you want is for someone to go “ooh I’ll have another glass of that”. And he said “oh you mean smashable – I can do that” and so he went out and created this. And it is exactly true to brief. Generous, approachable, a bit of a homage to Central Otago fruit.

WF: Other than that Matthew Jukes review, what is the best results you’ve had in terms of scores or awards?

AD: I was always in two minds about those competitions. And I noticed from a very early stage that the best operators here didn’t enter anything. But then I noticed that a few of them had entered earlier. A friend of mine — a New Zealand Master of Wine – Peter McCombie – became co-Chairman of the IWC – which has about 16,500 wines in it. I took the 2012 back to London and sat Pete down over lunch, and pulled out our very first vintage. I was nervous as hell and poured a couple of glasses. And Pete goes through his MW stuff, and he said “Now Andrew, what I’m going to say to you is either going to make you very happy, or very sad. I don’t think any of my panel chairs will pick this as a Central Otago Pinot Noir. I reckon they’re going to get stuck in Chambolle.” And I was like “Wow, that’s cool”.

And so I entered our 2013 as Peter really liked it, and it won a gold. And then the ’14 that we entered — he called me and said “Where are you?” And I said I was out walking — so he said “Sit down. We’re releasing the results tonight and you might be a bit surprised because not only has your wine won the New Zealand Pinot Noir Trophy, it has also won the International Sustainable Wine of the Year”. And then with the ’16, which was that classic year — we went one better and won the New Zealand Pinot Noir Trophy and the New Zealand Red Wine Trophy, and the Sustainable Wine of the Year again.

We didn’t so well in Decanter – I mean, we won golds and so on, but they judge differently. And I spoke to Nigel at length and said we were going to stop entering. And he has this view that is ‘never let anyone taste your wine blind’ and if possible you taste the wine with knowing the story. So then we started concentrating much more on getting it in front of the tough international critics. I think probably Rebecca is the meanest scorer.

WF: She’s certainly up there. And Jancis Robinson.

AD: Now my problem with Jancis is that she’s had the best Burgundies in the world poured down her neck day after day — for decades. So her criticism is way over there! And exceptional. I was talking to Matthew Jukes about how he ended up where he is and he said “The way I taste wines is that I don’t want to know anything about it – I just put it in my mouth. And then I’m looking for ‘is this delicious or is this fascinating?’ And he said “your wine is both delicious and fascinating — and that for me, is exceptional. And now I’m going to look at what is it made of, and how, and what is the story? The first thing I want to know is — do I find this delicious?”

We’ve always had big fans like Jamie Goode, who knows his New Zealand wines very well — and has spent an afternoon here actually. Anne Krebiehl MW who is excellent and some of the English operators. I find their notes very helpful. The scores are interesting. We’ve managed to get Rebecca into the 93-94 point range. The ’19 – Bob Campbell gave 96 points and so did Huon Hooke. James Suckling was here and was captured by the Felton Road magic which Blair and Nigel would always manage to orchestrate. The top six wines from him this year were four Felton Road and then both of ours. He went to Rippon and spent the afternoon there. He went to Prophets Rock and tasted that wine he does with Francois Millet. I have intentionally added a year more bottle age to our releases, because I just think our wine shows so much better after a year in the bottle. People are releasing their ‘21s now!

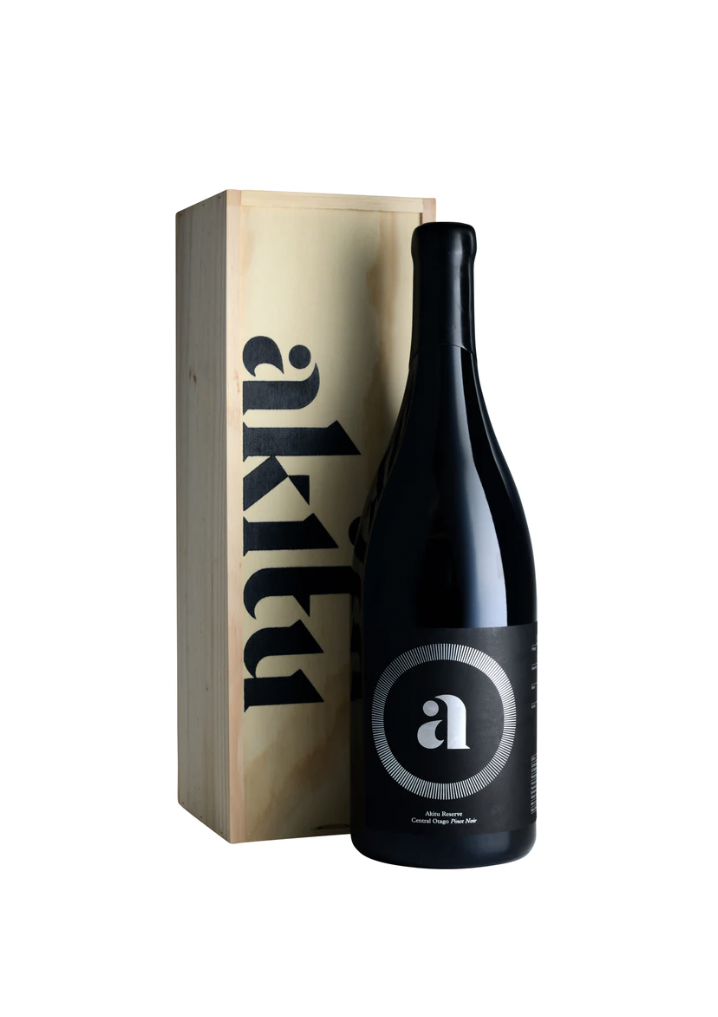

WF: I love your branding by the way. It’s really strong, and I look at the word, the way it is styled and I’m getting a mountainside? I loved it when I first saw it — there are a few imitators now — but it is unique. I can’t remember what the word Akitu means though?

AD: We were sitting there, and the sun was setting over there. And a friend of mine who is a Creative Director said “take a photograph of that” — and I do. And he said, take all the colour out of it, so it is just a silhouette — and he worked the A and K into it. We had the name but we didn’t have the logo. Akitu is ‘summit, or highest point’. And – we didn’t know this at the time — we discovered that is was an ancient Sumerian harvest festival?