It’s a beautiful morning for a visit – just after the celebrations for Felton Road’s 25th Anniversary – and I start with a walk in the vineyards. My colleague Curt Thomas hasn’t been down here for a long time, but his knowledge of New Zealand Pinot goes right back to the beginnings of Central Otago Pinot. We stroll out and to the left is Block 3 – arguably Felton Road’s most famous Pinot block. These vines are part of the slightly younger re-plant. When Block 3 was planted back in 1991, it was all on its own roots, which is a slightly risky proposition with phylloxera. In 2006 it was replanted with the Abel clone which was made famous through Ata Rangi. It is a clone that they really like as it holds its acid really well. And it is as close to a New Zealand heritage clone, apart from maybe 10/5, if you had to pick one.

In the vineyard I spy the new style of posts. For Organic certification you can’t use treated wood posts any longer. If you already have them in your vineyard it’s not a problem, but any replacements should be steel. They’re also using a new clone here – 943 – one of the latest batch of Dijon clones. Like Mendoza in Chardonnay – you get a high level of shatter and get seedless berries that are really small. In can make a really powerful wine with a rich character. As a stand-alone wine it can be a bit Zinfandel, but as a blending component it is really nice. I’m told that winemaker Blair Walter likes to think about blending in a way that you don’t want a vineyard-designate wine to taste of its clone – you want it to taste of its place.

The last few rows I pass are the old Block 3, which were planted in ’91, and these were taken from cuttings from Daniel Le Brun. They just call it their ‘Le Brun clone’. The vineyard thought it was 10/5 but it turned out to be something called 2/10, which is a clone that basically no-one uses any more. They like it as a point of difference. It generally shows really nice floral characters. The 10/5 from Block 3 can be very powerful, so this is used as a counterbalance.

I’m also keen to know what’s going on with the cover crops between the rows. At Felton Road the practice was to cultivate under the vines as they don’t have the option to use herbicide and eliminate any weed competition for the vine. The vineyard team would cultivate every second row and re-sow with cover crop each year… but having bought a new driller this year they can now drill new seed without having to turn the soil. They aren’t zero till, but are looking at something to avoid cultivating under the vines. The cultivation is down from about 60% to 20%.

We discuss the general feeling that the greater diversity of seed that you can put into the ground, the better you strike rate will be. If you’re increasing the bio-diversity in an environment, something will thrive. Their main three components would be a cereal, like a rye grass which is good for capturing carbon and fixing organic matter in the soil. Then legumes – in this case it is clover, which fixes nitrogen in the soil. If you’re fixing nitrogen every second row then you’re not having to put fertiliser down. And a little bit of compost – but that’s mainly as an innoculant for fungal life.

The company have four compost sites, and after the grapes are pressed off, the marc is returned to the site it came from. All of the grapes that are harvested here will end up in the compost pile at the back there. It’s another way that the Estate Manager can complete the circle. It is a biodynamic principle that you treat your farm as a single organism.

In Block 13 they have trialled the old methods of cultivation, which is where every second row it has been turned over; to compare and to see if there any benefits, whilst testing for soil carbon every third year. It’s not part of their carbon certification. At this point, through the IPPC you can’t, as a producer when you’re accounting for your carbon, claim sequestration in soils or in crops below a certain size. So trees have to be above five metres, and any carbon that is fixed in the vines or the soil, can’t be used as credit. The reason being it is that is a short term cycle and what gets fixed can be released quite quickly. If someone claims the soil carbon and then cultivates – they are releasing a whole load of that. It makes getting to net zero more challenging, but someone like Felton Road are not doing it for the badge.

Another thing that is being trialled in this block is to raise the fruiting wire about thirty centimetres, so that the fruit will mature slightly higher off the ground. It can be better for frosts, but also the grapes are ripening in a slightly cooler micro-climate and might hold their acid a bit better. Like most of the trials here, it might take about five years to decide if it works or not! There are also tressage trials across three of their sites this year. I’ve heard of this in Burgundy – at Domaine Leroy for example. It’s basically a form of braiding, and avoids cutting off the growing tip. There can be twin benefits to that – you avoid lateral growth and then with a bigger leaf area you don’t necessarily increase the rate of sugar accumulations as much as you increase the rate of phenolic maturation – so better flavour development at lower brix.

It is interesting to see the different ideas. And you can be sure that as one person is doing something one way – someone will be doing the complete opposite! Like whole bunch – some people love it and others say “Why would I do that to my wines?”

Felton Road can process something in the region of 150 to 180 tonnes of fruit and can do that quite comfortably with four people working not excessive hours. The winery design is all about flow. The fruit comes in and the main man on the forklift is Blair. The main reason for that is that it allows Blair to stay in contact with Gareth – who is the one bringing in the fruit. So, a constant dialogue about the fruit. How quickly it is coming off and whether the yield estimates are on target. He can then choose the appropriate size fermenter, of 32 available, to be as full as he can, without going too full. That way they don’t have to turn over tanks and don’t have to make a decision about when to press that is compromised.

We trundle down to the Barrel Hall, where everything is very tidy. Maybe that’s just because they’ve had the Celebration over the weekend, but probably not. The Pinot Noir Cellar has 390 barrels stashed away in it.

The Bannockburn Cellar was built to lengthen the ageing that wines could be given. Prior to that they needed to clear space for the next vintage. The Calvert and Block 5 tend to be the tightest in terms of tannin, so benefit from a slightly longer time in barrel. In terms of cooperage, the preference is Damy and Billon – both under the Bouchard Cooperage. The goal is to give a little tannic frame to the wine, but not influence it too aromatically. They get about eight years use out of a barrel, and when I was at the Cardrona Distillery I saw them maturing gin in old Felton Road barrels.

The Abel that they have at Cornish Point is one of eighteen clone and rootstock combinations at that site. Nigel had the vineyard before he bought Felton Road from Stuart Elms back in 2000, and it is planted in a very experimental way. It has the oldest Abel vines in Bannockburn. It’s one of the last picks at Cornish Point, and it can handle a bit more whole-bunch, so it is into the high end of the 20s. Felton Road would very rarely deviate from anything above 30%, and keep the level of new oak uniform across all of the blocks at about 25% new. There’s a spiciness to the Abel wine and a distinct black cherry note.

Compare that to the 10/5 at Cornish Point, which is largely planted on its own rootstock. Tried from the barrel where it is just post-malolactic fermentation, it is quite plush – glossy and rounded. Abel and 10/5 are the mainstay of the Cornish Point blend. The 667 clone from Calvert, from barrel, is one of the classic Dijon clones, and seems a little further down the track – more settled, and great softness to the body, and fresh florals.

Moving into the Chardonnay Cellar you can feel the increase in warmth, as they raise the temperature to encourage the last few through malolactic fermentation. They press the Chardonnay but then settle it for at least three days, as they’re not looking to take any solids to barrel. With the naturally high acidity in Central Otago, and the Mendoza clone having high levels of thiol, it can be a bit too astringent, so they use pretty clear juice. Felton Road are also one who avoid any new oak influence in the finished product. The older barrels are refurbished at a Cooperage in Marlborough, and the oldest they’re currently using is from 1999. There is the odd new barrel of course, but out of ninety barrels you can see maybe four new ones in the Cellar. Block 2 and Block 6 Chardonnays avoid any new oak at all.

There’s a small amount of Cornish Point Chardonnay – all originally Clone 95, but now has a little bit of Mendoza there too, as replacement vines have gone in over time. It is often the first block picked, of anything. They tend to be softer and show more stone fruit than a hard citrus that you might see in the Block 2. It shows a fair amount of exhuberance, and I am getting a bit of pithy grapefruit that balances out that stone fruit. Some nuttiness on the nose, and a bit of grip. On it’s own it is a winner – and to think that this goes into the Bannockburn blend!

They have seven barrels of it, so it would be about 10-15% of the blend. The rest of it is made up from picks at Elms, or blocks that don’t have their individual blocks – and then there is the new Chardonnay block down at Calvert. They didn’t get any fruit off there this year, but the next year will be the first year. Chardonnays from Block 2 show much stronger acid background – very, very different from Cornish Point.

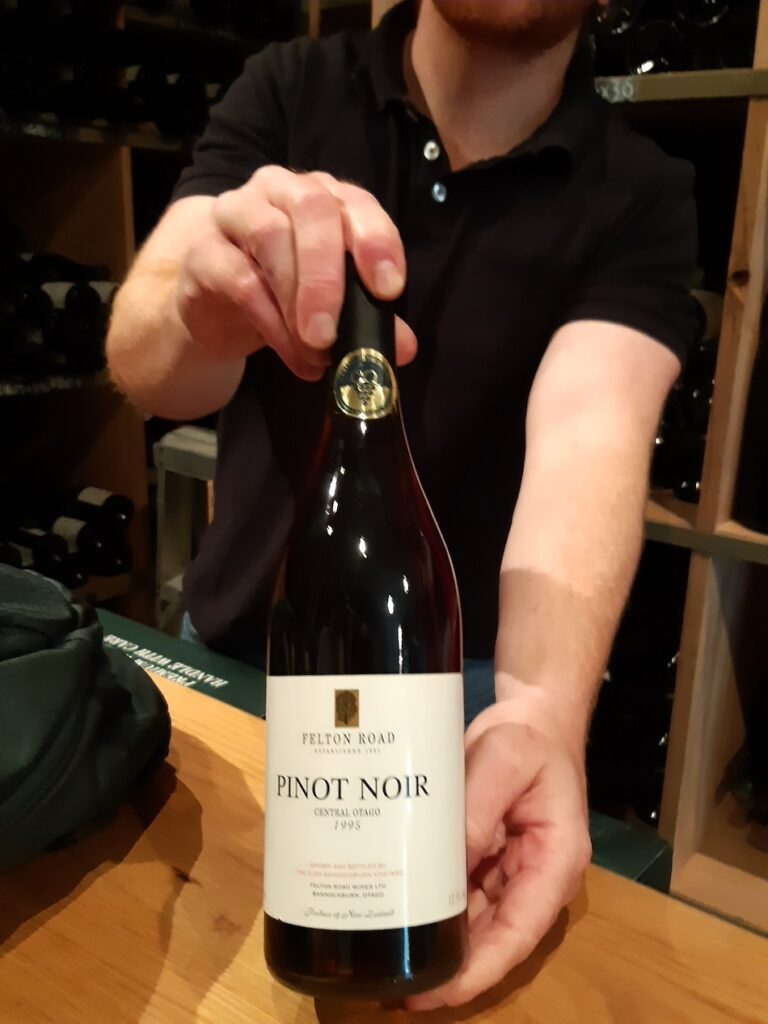

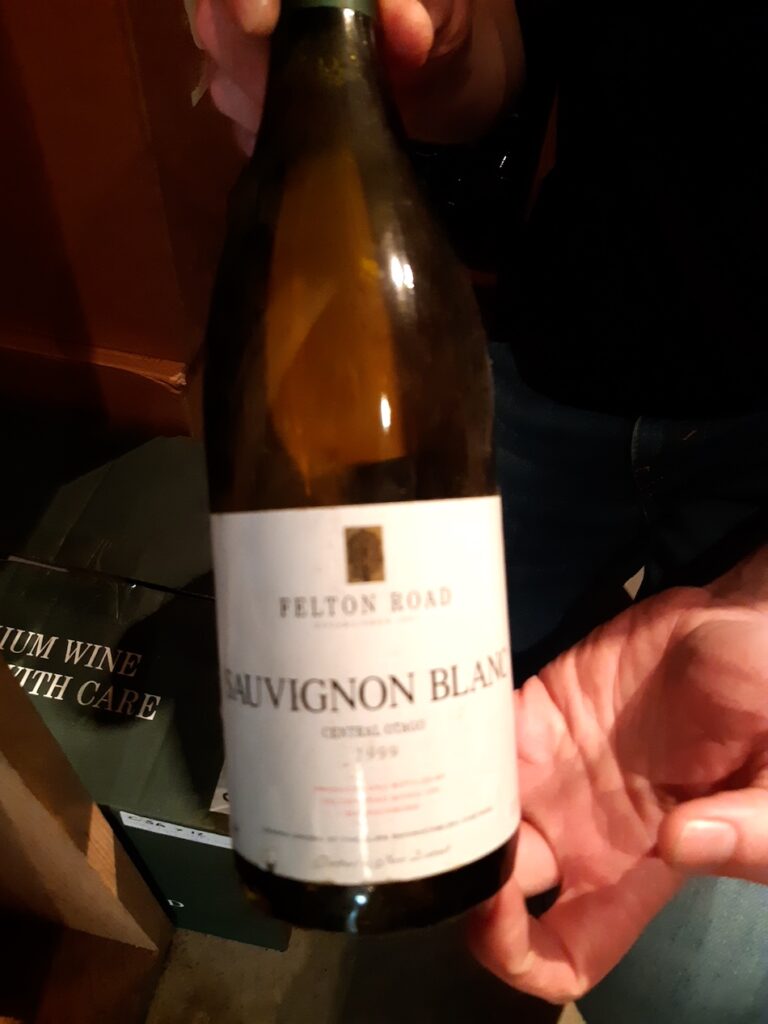

We move on to the Library and to look at some finished wines. They have more or less every wine that’s ever been made at Felton Road – in one format or another. Even back to the ‘95s which was the only Felton Road wine that wasn’t made on site – and a 1999 Sauvignon Blanc. There are three bottles of it left. Inside the room are also the most amazing amount of large format bottles. They bottle between 36 and 60 Jeroboams of the block wines each year, and they are very rarely offered for sale as they are kept for events and charity auctions. At the Celebration weekend, a Jeroboam of 2003 Block 3 was opened – and there is only one left.

Tasting through the current release Chardonnays – and starting with a Bannockburn Chardonnay 2021. Mostly from the Elms vineyard, with around four new oak barrels in the blend. A touch of peach with excellent acidity. It is really bright, easy and open – remarkably exhuberant, but then it is a young wine. Felton Road take the view that the Bannockburn is not ‘the last wine’ and every block is farmed to the same standard, then vinified to the same standard. From Cornish Point or Calvert there might be six or seven different fermenters, and likewise with MacMuir. Whilst they are tasted blind it isn’t a question of merit, but of typicity. They’re tasting the Cornish Point for “Cornish Point-ness”.

We then try the Block 6 Chardonnay 2021, and it dwarfs the Bannockburn expression, with huge drive and line of acidity. Lots of lemon and lime but with an almost Champagne base wine richness alongside that linearity. Both Block 2 and Block 6 are planted with Mendoza clone and are on their own roots – so the difference is a terroir expression. Block 2 sits on heavier soils, with a later bud burst and generally with lower temperatures. But the elevation gives it extra sunshine exposure and is perhaps the key to the richness.

On to Pinot Noir I start off with a Bannockburn 2021 and a Cornish Point 2021. 2020 had been such a cool year and produced firm, muscular wines. Straightaway the ’21s seem more perfumed and exotic, with the fruit dominating the grip of tannin. The Cornish Point has some chocolate and violets, with a drag of tannin across the palate. The length on the palate is wonderful. The MacMuir 2021 wine comes from ten year old vines. The standard of the wines that were made form 2019 and 2020 rather forced the winery’s hand in releasing this new Pinot Noir. This is my first taste of this – a good portion of the wine is from the Abel clone, with a bit of 828 and clone 5. It has the rich chocolatey character of a mature St. Emilion – almost claret-like, but with heaps of ‘red’ in it as well – raspberry, rosehip and with a glossy, slippery texture.

I get to try a couple of vintages of Block 5 – comparing the 2021 and the 2017 side by side; and then 2013 alongside the 2009, straddling a few interesting years of this great wine. The 2017 was the first 100-point score for Felton Road from Bob Campbell MW. The product of a really cool year – in New Zealand generally it wasn’t considered to be a great year – but Central was more protected from the weather, and had an overcast, cool vintage. I find those cooler years really deliver on depth of flavour and structure in Central Pinots. The ’21 is embryonic. Block 5 can be a potent wine and with the new bottles I often see a spike in the oak that can take a while to settle down. It has that classic ageing schedule where if you give it time to knit together it will reward you after ten to fifteen years.

2013 was a classic vintage across New Zealand, and 2009 another cooler year. Going back to 2009 – times were quite different for Pinot, with still a ‘bigger is better’ recipe for most wines. The 2013 is a very ‘complete’ wine, in a great spot – with heaps of generous fruit brightness. I think it would last in this amazing state for a few years yet.

At $100 a bottle, these aren’t everyday wines for most people, and Felton Road don’t aim to make ‘trophy wines’ – but wines that are to be enjoyed and shared. The aim of the winery is also to stay small – they won’t get any bigger than they are now. Once Nigel had bought the vineyards, he met Blair and said “well nine hectares is not financially viable, but how big can we get before we get too big?” and Blair replied “400 barrels”. That conversation was the impetus for the size of Felton Road.

A great wine is one that moves you when you taste it. It doesn’t happen very often. Personally, I’ve never tasted a wine that, for me, warrants a 100-point score. To me that represents perfection, and I haven’t had that yet. Sometimes the focus can be too much on that end result – and that magic number, but great winemaking is also about the vineyards – the soil is where great wine begins.